cause célèbre – Asia Bibi

Earlier this week Lord Alton of Liverpool tabled a question in relation to aid programmes and human rights pertaining in particular to the treatment of minorities in Pakistan.

Our Director, Lord Singh contributed to the debate. His full speech can be read below:

‘My Lords, I, too, congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Alton on securing this important debate, and pay tribute to the wonderful work that he does in the field of human rights. When India was partitioned in 1947, as we have heard, the founding father of the new state of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, then terminally ill, said that it would be a country that respected all its minorities. He did not live to see his hope tragically ignored. A rigid and intolerant form of Islam, Wahhabism, funded by Saudi dollars, now pervades the country.

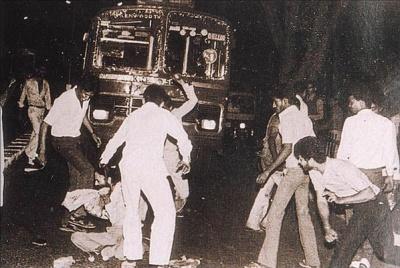

Strict blasphemy laws are used to prevent open discussion of religion, and the death penalty can apply to Muslims who try to convert to a different faith. As we have heard, a convert to Christianity, Asia Bibi, sentenced to death for alleged blasphemy, spent nine years on death row before eventually being allowed to flee to Canada. Others have not been so fortunate. In one case, children were made to watch as their parents were burnt alive in a brick kiln. Minorities are frequently allocated menial tasks such as the cleaning of public latrines. Homes of minorities are frequently attacked and women and girls kidnapped and converted or sold into slavery.

I have at times questioned the appropriateness of Pakistan, with its ill treatment of minorities, still being a member of the Commonwealth, a club of countries with historic ties to Britain. Members are required to abide by the Commonwealth charter, with core values of opposition to, “all forms of discrimination, whether rooted in gender, race, colour, creed, political belief or other grounds”.

By any measure, there is a clear case for expelling Pakistan from the Commonwealth, but this will not help its suffering minorities and could make their plight worse. The way forward is to look beyond charters and lofty declarations to clear targets and measures of performance for all erring members—Pakistan is by no means the only one—to nudge them to respect human rights. We must also target aid to specific projects geared to fight religious bigotry and prejudice. Pakistan is a country revered by every Sikh as the birthplace of Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith. He taught reconciliation and respect between different faiths. In this, the 550th year of the Guru’s birth, the Prime Minister Imran Khan, in welcoming Sikhs to visit the birthplace of their founder, stated his desire to move in this direction, and we owe it to Pakistan’s minorities to redouble our efforts to help him and nudge him to do so.’

The full debate can be read here: https://bit.ly/2S08ec8